Central Valley (California)

The Central Valley (also known as The Valley) is a large, flat valley that dominates the central portion of the U.S. state of California. It is home to many of California's most productive agricultural efforts. The valley stretches approximately 500 miles (800 km) from north to south. Its northern half is referred to as the Sacramento Valley, and its southern half as the San Joaquin Valley. The Sacramento valley receives about 20 inches of rain annually, but the San Joaquin is very dry, often semi-arid desert in many places. The two halves meet at the shared Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, a large expanse of interconnected canals, streambeds, sloughs, marshes and peat islands. The Central Valley is around 42,000 square miles (110,000 km2), making it roughly the same size as the state of Tennessee.

Contents |

Boundaries and population

Bounded by the Cascade Range, Trinity Alps and Klamath Mountains to the north, the Sierra Nevada to the east, the Tehachapi Mountains to the south, and the Coast Ranges and San Francisco Bay to the west, the valley is a vast agricultural region drained by the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers.

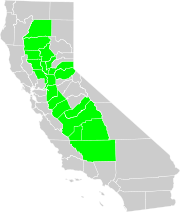

Counties commonly associated with the valley:[1]

- North Sacramento Valley (Shasta, Tehama, Glenn, Butte, Colusa)

- Sacramento Metro (Sacramento, El Dorado, Sutter, Yuba, Yolo, Placer)

- North San Joaquin (San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Merced)

- South San Joaquin (Madera, Fresno, Kings, Tulare, Kern)

About 6.5 million people live in the Central Valley today, and it is the fastest growing region in California. There are 10 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA) in the Central Valley. Below, they are listed by (MSA) population. The largest city is Fresno, followed by the state capital Sacramento.

- Sacramento Metropolitan Area (2,136,604)

- Fresno Metropolitan Area (1,002,284)

- Bakersfield Metropolitan Area (827,173)

- Stockton Metropolitan Area (664,116)

- Modesto Metropolitan (505,505)

- Visalia Metropolitan Area (410,874)

- Merced Metropolitan Area (241,706)

- Chico Metropolitan Area (214,185)

- Redding Metropolitan Area (179,904)

- Yuba City Metropolitan Area (165,081)

Geology

The flatness of the valley floor contrasts with the rugged hills or gentle mountains that are typical of most of California's terrain. The valley is thought to have originated below sea level as an offshore area depressed by subduction of the Farallon Plate into a trench further offshore. The San Joaquin Fault is a notable seismic feature of the Central Valley.

The valley was later enclosed by the uplift of the Coast Ranges, with its original outlet into Monterey Bay. Faulting moved the Coast Ranges, and a new outlet developed near what is now San Francisco Bay. Over the millennia, the valley was filled by the sediments of these same ranges, as well as the rising Sierra Nevada to the east; that filling eventually created an extraordinary flatness just barely above sea level; before California's massive flood control and aqueduct system was built, the annual snow melt turned much of the valley into an inland lake.

The one notable exception to the flat valley floor is Sutter Buttes, the remnants of an extinct volcano just to the northwest of Yuba City which is 44 miles north of Sacramento.

Another significant geologic feature of the Central Valley lies hidden beneath the delta. The Stockton Arch is an upwarping of the crust beneath the valley sediments which extends southwest to northeast across the valley.

Physiographically, the Central Valley lies within the California Trough physiographic section, which is part of the larger Pacific Border province, which in turn is part of the Pacific Mountain System.[2][3]

Flora

The 'Central Valley Grassland' is an important 'Nearctic temperate and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands' ecoregion in the Biome (ecosystem) of the earth. The Great Valley Grasslands State Park preserves this native grass habitat example in the valley.

Climate

The northern Central Valley has a hot Mediterranean climate (Koppen climate classification Csa); the more southerly parts in rainshadow zones are dry enough to be Mediterranean steppe (BShs, as around Fresno) or even low-latitude desert (BWh, as in areas southeast of Bakersfield). It is hot and dry during the summer and cool and damp in winter, when frequent ground fog known regionally as "tule fog" can obscure vision. Summer daytime temperatures reach 90 °F (32 °C), and occasional heat waves might bring temperatures exceeding 115 °F (46 °C). Mid Autumn to mid spring comprises the rainy season — although during the late summer, southeasterly winds aloft can bring thunderstorms of tropical origin, mainly in the southern half of the San Joaquin Valley but occasionally to the Sacramento Valley. The northern half of the Central Valley receives greater precipitation than the semidesert southern half. Frost occurs at times in the winter months, but snow is extremely rare.[4]

Tule fog

Tule fog (pronounced /ˈtuːliː/) is a thick ground fog that settles in the San Joaquin Valley and Sacramento Valley areas of California's Great Central Valley. Tule fog forms during the late fall and winter (California's rainy season) after the first significant rainfall. The official time frame for tule fog to form is from November 1 to March 31. This phenomenon is named after the tule grass wetlands (tulares) of the Central Valley. Accidents caused by the tule fog are the leading cause of weather-related casualties in California.

Rivers

Two major river systems drain and define the two parts of the Central Valley. The Sacramento River, along with its tributaries the Feather River and American River, flows southwards through the Sacramento Valley for about 447 miles (719 km).[5] In the San Joaquin Valley, the San Joaquin River flows roughly northwest for 330 miles (530 km), picking up tributaries such as the Merced River, Tuolumne River, and Stanislaus River.[6] A third, smaller river system, the Mokelumne River, drains a small area between the Sacramento and San Joaquin watersheds. In the south part of the valley, the alluvial fan of the Kings River has created a divide and resultantly the dry Tulare basin of the Central Valley, into which flow four Sierra Nevada rivers including the Kings. This basin, usually endorheic, formerly filled during heavy snowmelt and spilled out into the San Joaquin River. Called Tulare Lake, it is usually dry nowadays because the rivers feeding it have been diverted for agricultural purposes.[7]

The rivers of the Central Valley converge in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, a complex network of marshy channels, distributaries and sloughs that wind around islands mainly used for agriculture. Here the freshwater of the rivers merge with tidewater, and eventually reach the Pacific Ocean after passing through Suisun Bay, San Pablo Bay, upper San Francisco Bay and finally the Golden Gate. Many of the islands now lie below sea level because of intensive agriculture, and have a high risk of flooding, which would cause salt water to rush back into the delta especially when there is too little fresh water flowing in from the Valley.[8] The Sacramento River carries the vast majority of the runoff, about 30,215 cubic feet per second (855.6 m3/s), while the San Joaquin averages 10,397 cubic feet per second (294.4 m3/s) and the Mokelumne 644 cubic feet per second (18.2 m3/s). The water contributed by the rivers are relied on by over 25 million people.[9]

Engineering

The runoff from the Sierra Nevada and the resulting rivers that flow into San Francisco Bay provide some of the largest water resources of California. The Sacramento River is the second largest river to empty into the Pacific from the Continental United States, behind only the Columbia River and greater than the Colorado River.[10] Combined with the fertile and expansive area of the Central Valley’s floor, the Central Valley is ideal for agriculture. [11] Today, the Central Valley is one of the most productive farming regions of the United States, but water control was desperately needed to prevent rivers from overflowing during the spring and summer while drying to a trickle in the autumn and winter.[12] As a result, many large dams, including Shasta Dam, Oroville Dam, Folsom Dam, New Melones Dam, Don Pedro Dam, Friant Dam, Pine Flat Dam and Isabella Dam were constructed on rivers entering the Central Valley, many part of the Central Valley Project.[12] These dams have had a profound impact on the physical and ecological state of Central Valley rivers, including the loss of the chinook salmon.[13]

Rapid development and growth of California’s two major urban areas, the San Francisco Bay Area and the Los Angeles/Inland Empire/San Diego metropolitan areas, meant that an enormous new demand was placed on local water resources that were not enough to support the population alone. The Central Valley was looked to as a water source, leading to the creation of the California State Water Project which was contrived to transport water to parched, thirsty Southern California. [14] Runoff from the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers are intercepted in the delta by a series of massive pumps and canals, which divert water into the California Aqueduct that runs south along the entire length of the San Joaquin Valley. [15] The flow of the Sacramento River is further supplemented by a tunnel from the Trinity River (a tributary of the Klamath River, northwest of the Sacramento Valley) near Redding. [16] Cities of the San Francisco Bay Area, also needing great amounts of water, built aqueducts from the Mokelumne River and Tuolumne River that run east to west across the middle part of the Central Valley.[17][18]

Flooding

Most lowlands of the Central Valley are prone to flooding, especially in the old Tulare Lake, Buena Vista Lake, and Kern Lake beds. The Kings, Kaweah, Tule and Kern rivers originally flowed into these seasonal lakes, which would expand each spring to flood large parts of the southern San Joaquin Valley. Due to the construction of farms, towns and infrastructure in these lakebeds while preventing them from flooding with levee systems, the risk of floods damaging properties increased greatly. Major public works projects beginning in the 1930s sought to reduce the amount of snowmelt flooding by the building of large dams. In 2003 it was determined that Sacramento had both the least protection against and nearly the highest risk of flooding. Congress then granted a $220 million loan for upgrades in Sacramento County.[19] Other counties in the valley that face flooding often are Yuba, Stanislaus, and San Joaquin.

Economy

Agriculture is the primary industry in most of the Central Valley. A notable exception to the predominance of agriculture has been the Sacramento area, where the large and stable workforce of government employees helped steer the economy away from agriculture. Despite state hiring cutbacks and the closure of several military bases, Sacramento's economy has continued to expand and diversify and now more closely resembles that of the nearby San Francisco Bay Area. Primary sources of population growth are people migrating from the San Francisco Bay Area seeking lower housing costs, as well as immigration from Asia, Central America, Mexico, Ukraine and the rest of the former Soviet Union.[1]

Agriculture

The Central Valley is one of the world's most productive agricultural regions. On less than 1 percent of the total farmland in the United States, the Central Valley produces 8 percent of the nation’s agricultural output by value: 17 billion USD in 2002. Its agricultural productivity relies on irrigation from both surface water diversions and groundwater pumping from wells. About one-sixth of the irrigated land in the U.S. is in the Central Valley.[20]

Virtually all non-tropical crops are grown in the Central Valley, which is the primary source for a number of food products throughout the United States, including tomatoes, almonds,[21][22] grapes, cotton, apricots, and asparagus.

Four of the top five counties in agricultural sales in the U.S. are in the Central Valley (2002 Data). They are Fresno County (#1 with $2.759 billion in sales), Tulare County (#2 with $2.338 billion), Kern County (#4 with $2.058), and Merced County (#5 with $2.058 billion).[1] 2002 Data Sets

Early farming was concentrated close to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, where the water table was high year round and water transport more readily available, but subsequent irrigation projects have brought many more parts of the valley into productive use. For example, the Central Valley Project was formed in 1935 to redistribute and store water for agricultural and municipal purposes with dams and canals. The even larger California State Water Project was formed in the 1950s and construction continued throughout the following decade.

National Farmworkers Association (NFWA)

It was in the Central Valley, especially in and around Delano, that farm labor leader Cesar Chavez organized Mexican American grape pickers into a union in the 1960s, the National Farmworkers Association (NFWA), in order to improve their working conditions.

Social issues

San Joaquin Valley congestion

Since the 1980s, Bakersfield, Fresno, Visalia, Tracy and Modesto have exploded in both area and population, as housing values along the coast increased. Many people from Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area relocated to growing San Joaquin Valley suburbs in search of more affordable housing while retaining employment outside the Valley. This has led to traffic congestion between their Valley residences and their Bay Area employment with accompanying air pollution. Air pollution became a principal environmental and health concern as long ago as the 1960s, and resulted in the establishment of the California Air Resources Board in 1967. The San Joaquin Valley now has the worst air quality in California, along with the highest asthma rates.

Highways and infrastructure

Highways Interstate 5 and State Route 99 run, roughly parallel, north-south through the valley, meeting at its north and south ends. Interstate 80 crosses it northeast-southwest from Rocklin to Vacaville.

In addition to highways, the California Aqueduct follows I-5 from Tracy on southwards to Southern California across the Transverse Ranges and the federal Central Valley Project includes numerous facilities between Shasta Dam and the Grapevine. PG&E's and Western Area Power Administration's system of three 500 kV wires (Path 15 and Path 66) run through the valley. Path 26 also runs in the southernmost part of the San Joaquin Valley and is used to transfer power from PG&E service territory to Southern California Edison territory on hot summer days.

BNSF (Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway) and Union Pacific Railroad both have railway lines in the Central Valley. The BNSF Bakersfield Subdivision runs from Bakersfield to Calwa, four miles south of Fresno. From Calwa the BNSF Stockton Subdivision continues to Port Chicago, west of Antioch. The Union Pacific Railroad Martinez Subdivision runs from Port Chicago through Martinez, Richmond and Emeryville to Oakland. The UP's Fresno Subdivision runs from Stockton to Sacramento. Amtrak operates six daily San Joaquins trains over these lines.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "A Statistical Tour of California's Great Central Valley". California Research Bureau. California State LIbrary. http://www.library.ca.gov/crb/97/09/. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ "Physiographic divisions of the conterminous U. S.". U.S. Geological Survey. http://water.usgs.gov/GIS/metadata/usgswrd/XML/physio.xml. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ↑ Benke, Arthur C.; Cushing, Colbert E. (2005). Rivers of North America. Academic Press. pp. 554. ISBN 0120882531.

- ↑ "Climate of California". Western Regional Climate Center. .www.wrcc.dri.edu. http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/narratives/CALIFORNIA.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ "Sacramento River Basin National Water Quality Assessment Program: Study Unit Description". United States Geological Survey. ca.water.usgs.gov. http://ca.water.usgs.gov/sac_nawqa/study_description.html. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ "Restoring the San Joaquin River: Following an 18-year legal battle, a great California river once given up for dead is on the verge of a comeback". Natural Resources Defense Council. www.nrdc.org. 17 September 2007. http://www.nrdc.org/water/conservation/sanjoaquin.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ Gorelick, Ellen. "Tulare Lake". Tulare Historical Museum. www.tularehistoricalmueseum.org. http://www.tularehistoricalmuseum.org/articles/tularelake.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ "Delta Subsidence in California: The sinking heart of the State". United States Geological Survey. ca.water.usgs.gov. http://ca.water.usgs.gov/archive/reports/fs00500/fs00500.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ "Sacramento-San Joaquin River System, California". American Rivers. America's Most Endangered Rivers Report: 2009 Edition. http://www.americanrivers.org/our-work/protecting-rivers/endangered-rivers/sac-san-joaquin.html. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ The Columbia is the largest, with an average discharge of 265,000 cfs. The Sacramento comes next with a flow of 30,215 cfs, and even though the Colorado is much longer, its discharge is only about 10,000-22,000 cfs (that is before diversions started; the river is currently dry at the mouth). Other significant rivers include the Klamath (17,010 cfs), Skagit (16,598 cfs), Snohomish (13,900 cfs), and San Joaquin (10,397 cfs).

- ↑ "California’s Central Valley". National Public Radio. 2002-11-11 to 14. http://www.npr.org/programs/atc/features/2002/nov/central_valley/. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Stene, Eric A.. "The Central Valley Project: Introduction". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. http://www.usbr.gov/history/cvpintro.html. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ "Ecosystem Restoration: Systemwide Central Valley Chinook Salmon". CALFED Bay-Delta Program. http://science.calwater.ca.gov/pdf/eco_restor_all_salmon.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ "California State Water Project Overview". California State Water Project. California Department of Water Resources. 2009-04-15. http://www.water.ca.gov/swp/. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ "California State Water Project Today". California State Water Project. California Department of Water Resources. 2008-07-18. http://www.water.ca.gov/swp/swptoday.cfm. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ Anderson, David (1999-07-04). "A temporary diversion". Times-Standard. http://sunnyfortuna.com/explore/trinity_diversion.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ "The Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct". Aquafornia. 2008-08-19. http://aquafornia.com/where-does-californias-water-come-from/the-hetch-hetchy-aqueduct. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ "Mokelumne Aqueduct". Aquafornia. 2008-08-19. http://aquafornia.com/where-does-californias-water-come-from/the-mokelumne-east-bay-aqueduct. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ "Sacramento Flood Protection". http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/summary_0199-705251_ITM.

- ↑ Reilly, Thomas E. (2008). Ground-Water Availability in the United States: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1323. Denver, CO: U.S. Geological Survey. p. 84. 978-1-4113-2183-0.

- ↑ Purdum, Todd S. (2000-09-06). "NATIONAL ORIGINS: CALIFORNIA'S CENTRAL VALLEY; Where the Mountains Are Almonds". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950DE7DD1639F935A3575AC0A9669C8B63&n=Top%2FReference%2FTimes%20Topics%2FSubjects%2FC%2FCooking%20and%20Cookbooks. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ Michael Pollan

External links

- Central Valley Tourism Association

- CA Central Valley & Foothills, project area of the American Land Conservancy

- Great Valley Center

- Valley Vision

| California Central Valley grasslands | United States |

| Canadian aspen forests and parklands | Canada, United States |

| Central and Southern mixed grasslands | United States |

| Central forest-grasslands transition | United States |

| Central tall grasslands | United States |

| Columbia Plateau | United States |

| Edwards Plateau savanna | United States |

| Flint Hills tall grasslands | United States |

| Montana valley and foothill grasslands | United States |

| Nebraska Sand Hills mixed grasslands | United States |

| Northern mixed grasslands | Canada, United States |

| Northern short grasslands | Canada, United States |

| Northern tall grasslands | Canada, United States |

| Palouse grasslands | United States |

| Texas blackland prairies | United States |

| Western short grasslands | United States |

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||